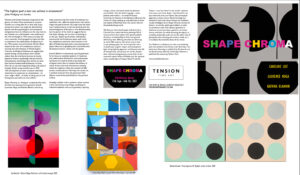

SHAPE CHROMA. 18th September-16th October 2021

By Sue Hubbard

The highest goal a man can achieve is amazement

Johan Wolfgang von Goethe.

Newton and Goethe famously disagreed on the genesis of colour. Most commentary assumes Goethe was wrong. But this is true only if you accept that colour can simply be described by physics and that psychological and conceptual components have no influence on the way that we see. Goethe was a philosopher who understood the drift of thought in 19th century Europe. He was a romantic who’d grasped an important flaw in empiricism: the impossibility of objectivity. In the 19th century the art historian Charles Blanc explored the laws of ‘simultaneous contrast’, drawing from the theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Eugène Delacroix, to suggest that optical mixing would produce more vibrant colour than the traditional process of mixing pigments. Science, psychology and, particularly, contemporary technology have moved on since then but the fundamental dichotomy remains. How do we see and respond to shape and colour? As Jules Olitski wrote in Artforum in 1967, “the development of color structure ultimately determines its expansion or compression – its outer edge. I think…of color as being seen in and throughout, not solely on, the surface”.

Shape Chroma, is a ‘trialogue’ curated by the artist Caroline List between three painters: herself, Laurence Noga and Katrina Blannin, who bring these questions into the realm of contemporary aesthetics with different explorations into colour, shape and spatial illusion. No single issue has been more fundamental to modernist painting than the acknowledgment of flatness or two-dimensionality but the power of the mark to suggest illusion and depth belongs not so much to painting as to the eye. Exploring chromatic interactions, constructed and illusionistic space, each artist has created new painterly conversations in the light of Modernist abstraction and contemporary digital influences, highlighting the Goethe/Newton dichotomy between reason and the poetic.

Katrina Blannin’s meticulously layered geometric forms focus on complex systems of repetition and mathematics. Palindromic and isochromatic structures are used to produce paintings full of logical clarity that re-examine the history of colour theory and early Renaissance painting, which she explores within the context of 20th century constructivism. Working with acrylic on a medium textured linen she generates fresh debates around the possibilities for the painted surface.

Nostalgia collides with a synthetic colour palette in the work of Laurence Noga, combining an industrial aesthetic with pure geometry. Layering collage, colour and mixed media he plunders memorabilia from his father’s garage – tools, packets and washers – to evoke Proustian memories. An interest in the Bauhaus influences his choice of colour, setting up unpredictable surfaces and depths of field that draw the viewer into his discombobulating world.

Working on linen, board, paper and aluminium Caroline List creates luminous paintings full of sensuous hues that explore the spatial qualities of colour in relationship to form and ground, defined by their differing absorbances. Drawing on early 20th century abstraction and virtual screen photography her work implicitly refers to landscapes, organic shapes and atmospheric light. Using high key pigments and fluorescents full of transparency and opacity her works, despite their sophisticated geometry, create links to the saturated colour fields of Rothko and the spiritual, other worldly light of Caspar David Friedrich.

Colour is not ‘out there’ in the world – painted onto roses and snow drops – but formed in our eye, mind and, even, our hearts. Our perceptual apparatus creates colour filtered through our emotional state and cultural biases. An ambitious, visually intelligent show Shape Chroma revisits art history to revivify what’s gone before in order to construct a new 21st century grammar in which to re-examine these questions of colour theory and form. So whilst knowing the physics is, certainly, technically useful, it’s on the other side of perception that meaning and artistry reside, as is articulately illustrated by these three artists.

Sue Hubbard is a freelance art critic, award-winning poet and novelist. A main feature writer for Artlyst, her latest novel, Rainsongs, is published by Duckworth and her fourth poetry collection, Swimming to Albania, is published this autumn by Salmon Press.

www.suehubbard.com

2021 – Vanderlove letter – Swiss Contemporary art journal straddling art reproduction and pocket gallery , The Vanderlove Letter is an exhibition space entirely devoted to works and published quarterly.

Caroline List

2021- Rise Art – On line artist focus

https://www.riseart.com/article/2390/the-landscapes-of-sublime-abstraction

Sublime / (sub)liminal: dicing with doubles and shadow-play in the work of Caroline List written by Richard Dyer.

Solo show ‘DITTO DITTO’ 2004 at Catto Contemporary/ Hoxton, London

Richard Dyer 2004

The runner wins the race; the moment of the tape breaking, in that instant, pain is transformed into pleasure, the “sublime moment”. In Ditto Ditto Caroline List phototropically irrigates the Kantian notion of the sublime. In Kant’s Critique of Judgement he unloads the notion of the sublime from the concept of the beautiful1. That which we would term the sublime arises not from the object of contemplation, but from the subjective experience of the observer, their response to the object. The sublime lies in the territory of feeling, it cannot be explained by reason or logic, as Lyotard states: “The admixture of fear and exaltation that constitutes sublime feeling is insoluble.”2

Kant deems the “beauty” in the beautiful to be “purposiveness without purpose”, Zweckmässigkeit ohne Zweck; organisation, symmetry, harmony of colour and form; attributes of the useful but serving no purpose. Conversely the sublime stems from the principal of disorder, perposivelessness, an encounter with that which cannot be contained, organised, explained; the limitless; that which cannot be figured by reason, and thus induces a sense of terror and pain, a pain which is transformed into joy at the “sublime moment”, when we embrace our impotence in the face of the ineffable and infinite force of nature.

Burke stated of the sublime that “…its strongest emotion is an emotion of distress”3 and Kant rightly charged him with not taking his argument far enough, it is this very distress, this fear in the face of the mighty which makes the sublime so attractive, precisely because we are untouched by it, we are an observer, safe in the haven of reason.

The Romantic movement of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century was profoundly shaped by the notion of the sublime as expounded by Burke, and in the first French translation of On the Sublime (1674) attributed to Longinus. As with the critical concepts of structuralism and postmodernism in the twentieth-century, the sublime and the more general notion of the romantic were first associated with literary and poetic criticism, and only later came to be applied to the visual arts.

Although Romanticism is a historical term referring to a specific period and particular texts and images – from Milton to Delacroix – it continues today not only as a term applicable to certain individual artists; Kiefer, O’Donahugh, Paladino, but also to certain tropes exploited by the advertising and image generation industry. Image banks, with their endless arrays of perfect bodies in perfect environments at perfect moments are sourced by photo-researchers for advertisements, books, public information booklets, pamphlets, magazines and newspapers; the whole veneer of seduction that constitutes the visual matrix of aspirational imagery which forms the plasma of the post-industrial socio-political environment4.

The engine of production, in search of a “quick-fix” image to represent an ideal of pleasure, ecstasy, fulfilment, perfection, or desire, uses images of perfect blandness; fully saturated colour, high-resolution printing, sharp-edged shadows, clean, clear textures, bright high-angled lighting, over-toned, trim and tonsured bodies clad in the mantel of synthetic sartorial seamlessness, the shiny skin of the postmodern, perfect, featureless and micro-thin. List takes these ersatz projections of the quintessential moment of the sublime – the moment of suspension in the air before plunging into deep blue water, the second of releasing a ball at high speed, reaching the summit of a mountain, the bliss of a first kiss – and subjects them to a tripartite process which performs a semiotic excavation of content and meaning, uncovering their subconscious alignment to the concept of the romantic sublime.

First the image is printed in black and white onto a canvas which has already been prepared with coloured pigment, then the image is doubled, tripled, or even quadrupled and reversed, to form the impression of a series, a reflection, and finally it is worked over with more paint, augmenting, concealing or mutating the image beneath. Warhol would paint sections of his canvas in different colours before overprinting it with a photographic silk-screen image, at this point the process ended. By taking it one step further and painting into the photograph again List inverts the history of the influence of photography on painting and initiates a rich discourse of image, meaning, method and morphology. First there was painting, then photography; to begin with photography tried to imitate painting, then painting tried to imitate photography, now both practices are conflated in List?s work in a hybridised form which is neither painting nor photography, and yet is both.

By trapping the chemical skin of photography between the layers of paint List develops a dynamic dialogue between the two modes of representation. We must remember that these are not just silk-screened images, but actual photographs, the canvas – that most traditional support for oil painting – has actually been coated with photographic emulsion and exposed to the image in the dark-room, developed, washed and fixed; the delimiting aspects of photography are smuggled into the conventional arena of the easel painting, while at the same time the denotative signifiers of oil-painting trap in their wafer-thin interstice the veneer of photography. This praxis is in opposition to that of the photorealist painter whose “subject” is the photograph itself.

For List one of the most important aspects of photography is its infinite reproducibility. The evaporation of the “aura” of uniqueness and authenticity as posited by Benjamin5 due to the endless proliferation of images since the invention of photography is here exploited to conjure the “double”, Jung’s “Shadow”6 the repressed, unconscious aspects of the personality; instinctual, creative, but uncanny and troubling – it can be seen as the psychic concomitant of the physical structure of the cerebellum, our primitive “reptilian” brain. It is this aspect of the psyche which responds to the sublime, an ur-verbal “knowing” which bypasses, or even short-circuits the reason-based functioning of the conscious, rational mind. It is through the shadow, our inner double, that we encounter the sublime.

List’s doubles are usually mirror images, in such works as How Does it Feel to be You, With or Without You, We and Falling (all 2001–2002), the artist inverts the figure, confronting it with its mirror image. Reproduction invokes an un-nameable anguish, an uneasiness before the mirror-image, the evocation of “the uncanny” through the presence of the simulacrum7 to confront the shadow is to question the reality of “the real”, when we are confronted with the sublime.

Bold, overhanging, and as it were threatening rocks; clouds piled up in the sky, moving with lightning flashes and thunder peals; volcanoes in all their violence of destruction; hurricanes with their track of devastation; the boundless ocean in a state of tumult; the lofty waterfall of a mighty river… as in Kant’s examples, our notion of the real, as encountered in the safety of “the everyday” is shattered, buckled by the might of nature in extremis.

The caesura where the image and its virtual shadow meet – Vanishing Point, Rock Girl, With or Without You (all 2001–2002) – is the site of the limen, the liminal, where consciousness gives over to the shadow in order to experience the sublime. Usually the sublime is subliminal, literally sub-liminal, below the threshold of consciousness, sublimated into the territory of the Kitsch – the sunset postcard, the “beautiful” flower painting, the electronically animated waterfall picture – but it is here, at this fissure between the real and the hypereal, the conscious and the subconscious, the self and the other, that occurs the integration of the shadow with the self, nature with the human, the ineffable with its coagulation in the real; the sublime moment.

Richard Dyer © 20

Richard Dyer is assistant editor at Third Text: Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture and art editor of Wasafiri, the magazine of international contemporary writing.

He was news editor and London correspondent for Contemporary magazine for over ten years. He is a widely published art critic, reviewer, poet, fiction writer and also a practicing artist.

His critical writing has appeared in Contemporary, Frieze, Flash Art, Art Review, Art Press (London correspondent), Third Text, Wasafiri, PLUCK, The Independent, The Guardian, Time Out, Citizen K (London correspondent), Rapid Eye, Performance Magazine (assistant editor), The Jewish Chronicle and many other publications and catalogues.

Publications include: Electronic Shadows: The Art of Tina Kean (Black Dog, 2004); Dan Hays: Impressions of Colorado (Southampton City Art Gallery, 2006); Riddled With Light: Corpus Lumen: Susie Hamilton, 1996–2000 (Paul Stolper, 2006), Zineb Sedira: Saphir (Photographer’s Gallery, 2006) and Transitive Transduction: Breaking the Integument in the work of Tony Bevan (Ben Brown Gallery, 2006).

His latest publications are Controfacciata: Solid Water, Liquid Stone, on the work of German photographer Matthias Schaller (Ben Brown Gallery, London, 2008), Keith Coventry: Deconstructing the Modernist Utopia (Haunch of Venison, Zurich, 2008), Making the (In)visible in the Work of Mark Francis (Lund Humphries, 2008), Painting: The Essential Verb (Jerwood Foundation, Contemporary Painters Prize, 2008), The Descent of Man: Wolfe von Lenkiewicz (All Visual Arts, 2009); Clement Page: Screen Memories: Picturing Lost Time in the Watercolours of Clement Page (Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin, 2009); Art on Demand: Custom Colours and Materials: Sébastien de Ganay, Abstract Works Catalogue, 2008–2009 (onestar press, 2009); Demi-Monde: Alexander de Cadenet (F-ish Gallery, 2009) and Valérie Jolly: Infra-Thin (Alexia Goethe Gallery, 2010).

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement, [1790], J.H.Bernard, trans., Hafner Press, MacMillan Publishing Co, Inc, New York, 1951

- Jean-François Lyotard, Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, Elizabeth Rottenberg, trans., Stanford University Press, 1994

- Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, [1757], Adam Phillips, ed. and intro., OUP, Oxford, 1990

- John Berger, Ways of Seeing, British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, London, 1972

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, [1935], in Illuminations, Cape, London, 1970

- C.G.Jung, “The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious”, in Collected Works, vol 9, R.F.Hull, trans., Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd, London, 1951

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulations, Paul Foss, Paul Patton and Philip Beitchman, trans, Semiotext(e), Inc, New York, 1983